National Service in the Royal Army Medical Corps

Dr John A Lunn • Captain • RAMC • 1955-1957

In the Middle East and Cyprus

1956 and 1957 were the peak years of the EOKA campaign. The total British servicemen killed throughout the entire campaign was 371. Many were caused by ambushes of Army vehicles and high up in the mountains the terrorists had ample time to prepare for an attack as the Army vehicles had a characteristic whining sound as they came up the mountain roads in low gear. Severe gunshot and bomb wounds were sadly all too frequent, but I was in awe and respect at how the young National Servicemen coped with their injuries. Once when I was duty officer there was a young Scotsman whose leg had been blown off by a roadside bomb. As I approached his bed I was in great difficulty to know what to say to him. Wonderful guy that he was he broke the ice and before I uttered a word, he said "Aren't I lucky, no more bloody drill for me!" He broke into a great big grin and we then had a wonderful and relaxed chat. He of course had helped me and not the other way round!

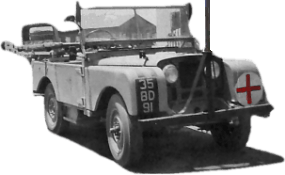

All deaths were tragic beyond words, but some more than others. One such was a young Royal Marine officer who had been dreadfully mutilated by a hand grenade which had exploded in his lap when he was travelling in a land rover. This was on a Tuesday and four days later, on the coming Saturday, he was to have been married. Another incident, again as duty officer, was when I was woken at about 3.00 am in the morning to be told a report had come in of a Land Rover with five Royal Marines in it having been ambushed in the Troodos mountains. All were reported to be alive but at least one very badly wounded. I alerted all the theatre staff and Col. John Watts, the distinguished war surgeon. All were in place to receive the casualties when they arrived at the BMH. The sergeant had an amazing escape from death, one bullet having gone through the lobe of his left ear and another through the top of his beret! The officer had very severe abdominal wounds and was taken to the theatre first, Thanks to John Watts' skill he survived. The senior NCO was admitted to the surgical ward to await going to the theatre. Initially he didn't appear too badly wounded but on returning to check how he was it was obvious his condition had deteriorated badly and his blood pressure critically low. I at once put up a drip and in the end it all turned out well for him. One subsequent coincidence was that he was flown back to the UK for completion of treatment and was put on the surgical ward at St. Thomas's Hospital where my sister, Hilary, was working. She recognised my writing and told the NCO who it was that had helped him. He then said I had saved his life. Although not exactly accurate, I was at least part of the team that had.

In those days the Army did not pay to bring dead soldiers back home and they were buried in Cyprus. From time to time, after a burial, the relatives had collected the considerable sum of money needed to fly a lead lined coffin back to the UK. In such circumstances the dead soldier had to be exhumed, his comrades having the grim task of doing so, and I as a medical officer accompanied the sad event. Before the body could be flown home, it had to be embalmed in order to comply with regulations in place at that time. John Turk and I had to do research on how to do this, and it was one of the most unpleasant tasks I ever had to do.

One week end a forest fire broke out in the Troodos mountains and it was so severe that the Cypriot fire brigade was unable to cope with it and troops were sent in to help. Tragically with no training for this twenty one of them were burnt to death. The fire spread so quickly and strongly that it would leap across a valley so that a soldier running away from the fire and having to go down and up the other side of a valley would find the fire already on the side he was running into. One party from the Norfolk regiment was saved as the officer knew that the fire travelled about a foot and a half above ground and by lying flat on the ground as the fire approached, the party was saved as the fire passed safely over their heads. The twenty one dead were brought back to the BMH and put in a large hut for identification. Dental records from the UK were needed to identify some, so badly disfigured were they. One interesting point about the fire travelling about a foot and a half above ground was that some soldiers although their clothes were burnt off their bodies, there was one exception in that their boots and socks remained intact. Working in the hut with the twenty one burnt bodies and checking out dental records for those who were totally unrecognisable, with an appalling smell, was a grim task for me but even more so for the two young RAMC corporals who had been delegated to help. They performed magnificently. Afterwards the Commanding Officer called me in to see him and he said he had put in a special commendation for the two corporals which was thoroughly deserved by them. He told me that he would not be doing anything for me as what I had done was just part of my normal duties! I thanked him and duly left his office not quite sure what I had to be grateful for!